Lasauvage, now a peaceful village nestled in the heart of a wooded valley, was once a major steel production site. This year marks the 400th anniversary of the site’s founding, a history shaped by periods of prosperity, crises, and major transformations.

The beginnings: Gabriel Bernard and the first installations

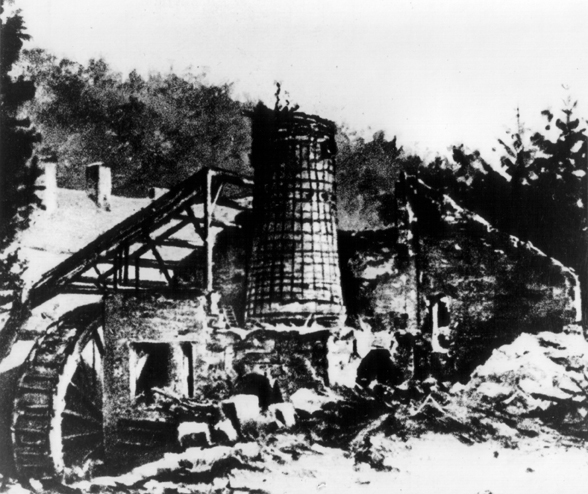

In 1625, Gabriel Bernard, a bourgeois from Longwy and master of the forges in Villerupt, had a blast furnace and a forge built in Lasauvage. It was one of the first blast furnaces in the country, and the only one in the south at the time, marking the beginning of the region’s steelmaking history.

Why Lasauvage?

Despite its isolation, the site offered three essential resources for the steel industry of the time:

- Iron ore, initially mined in alluvial form (surface ore containing up to 50% iron, compared to around 30% in the “minette”, extracted in tunnels).

- Wood from the surrounding forests, used as fuel.

- Water from the Crosnière, providing hydraulic power.

However, the Thirty Years’ War devastated the region, and the population was decimated by epidemics and famine. In 1646, a French invasion destroyed the facilities, and the village was abandoned. Gabriel Bernard died heavily in debt.

From renewal to industrial prosperity

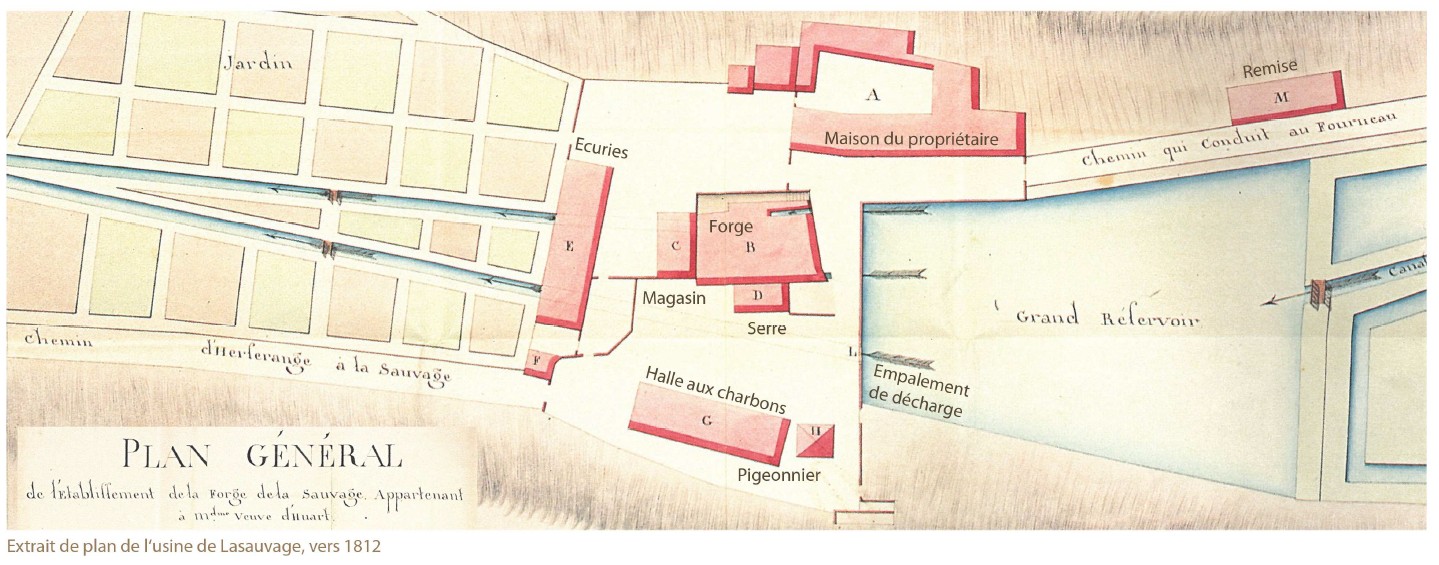

In 1650, François Thomassin took over the estate and brought together several sites, including the Herserange forge, the Athus furnace, and the Moulaine platinum refinery, thereby forming the largest metallurgical complex in the region.

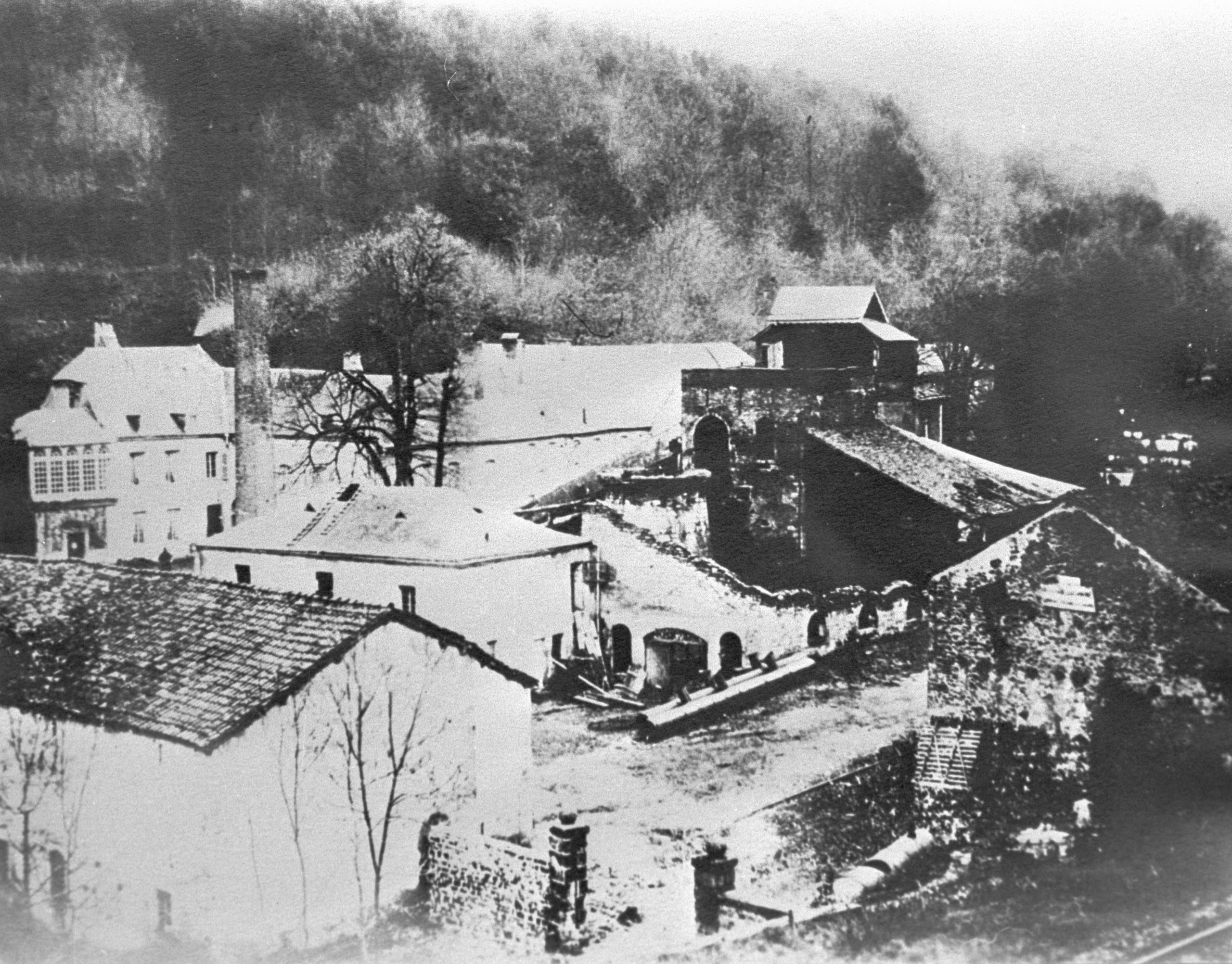

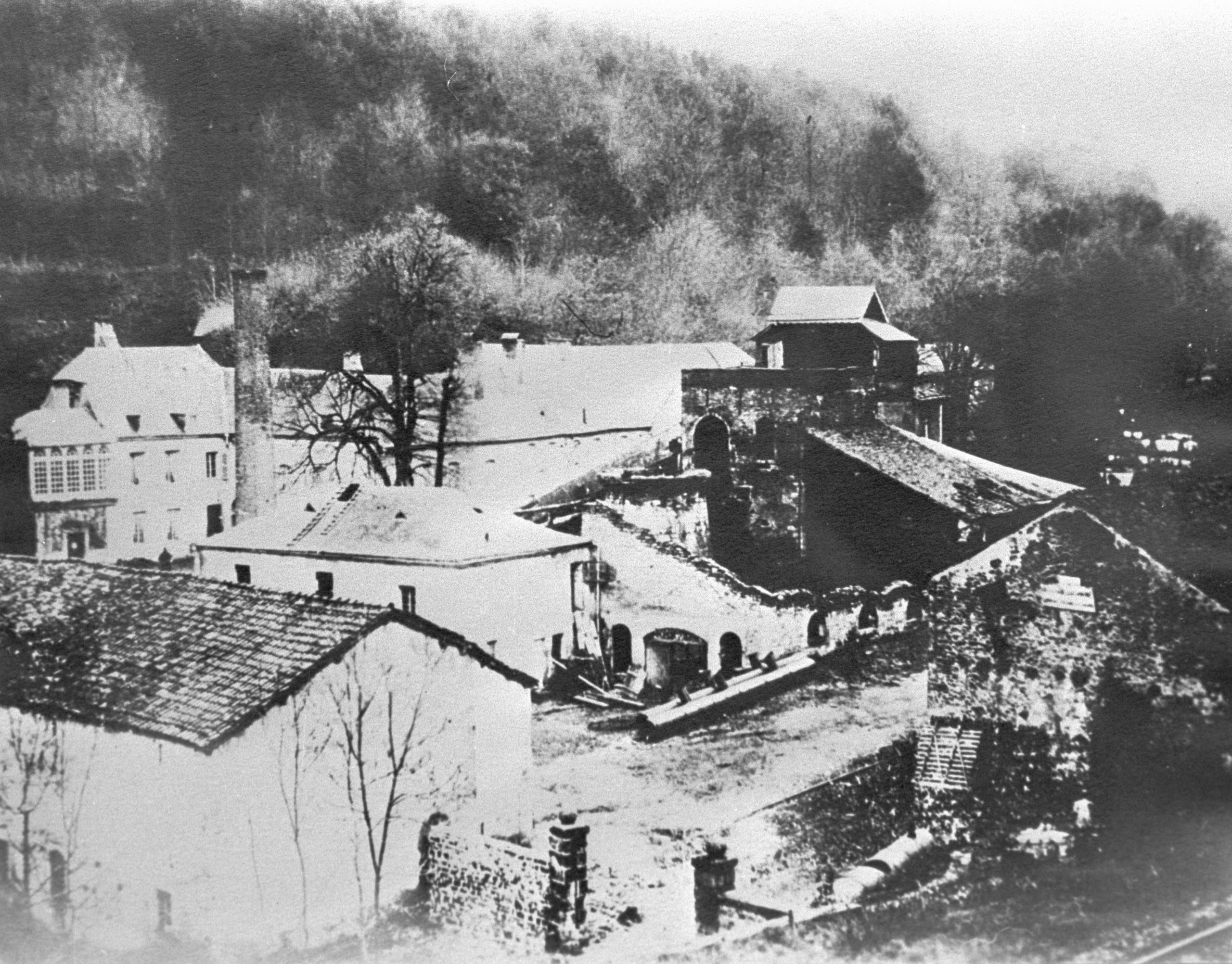

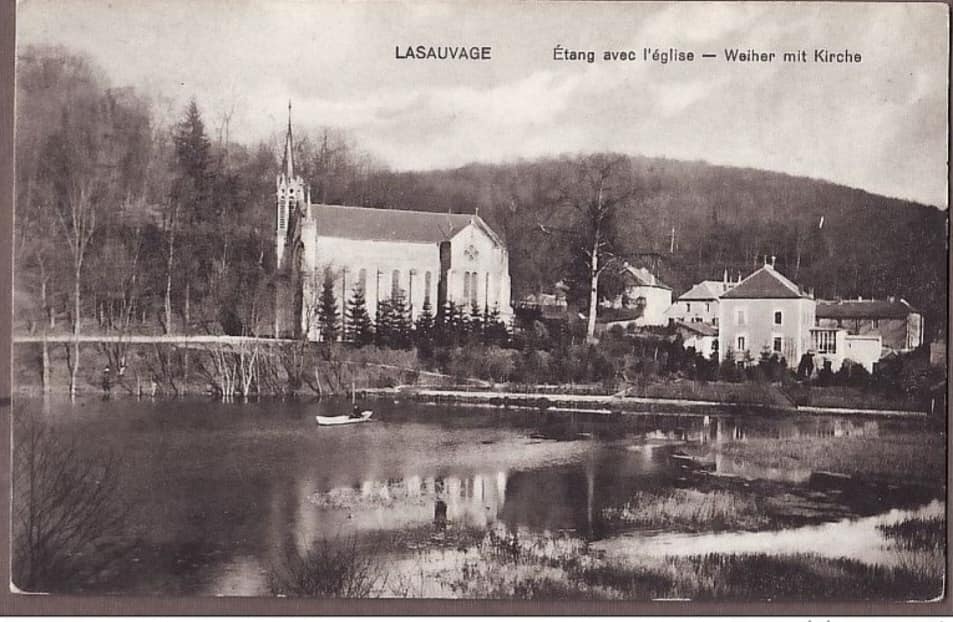

After a succession of more discreet owners, Henri Huart took the reins in 1751. He left his mark on the village by building an elegant mansion opposite the blast furnace, known as the “Château” of Lasauvage. Although its architecture does not resemble that of a true castle, it has retained this title to this day.

Expansion and limits of the industrialization

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 disrupted the organization of the site by dividing it in two: the furnace ended up in Luxembourg, while the warehouses and outbuildings remained in France. This issue was settled in 1820 by the Treaty of Courtrai.

Industrial growth continued with the installation of a second blast furnace in 1841, followed by a third in 1847. However, only two were operated simultaneously:

- A wood-fired furnace producing three tons of cast iron per day (abandoned in 1869).

- A coke-fired furnace producing twelve tons per day.

Until then, the furnaces had been supplied with surface alluvial ore. In 1841, an initial attempt was made at underground mining, but environmental restrictions limited the initiative. It was not until the 1880s that the underground extraction became significant.

Throughout the history of the blast furnaces in Lasauvage, transportation remained the main challenge. Nestled at the bottom of a steep valley, the village was difficult to access, making any railway connection with Luxembourg impossible. On the French side, the Grand Duchy’s membership of the Zollverein (German Customs Union) further complicated trade, as ore exports were subject to heavy taxes and formalities.

While the rest of the country benefited from the development of the railway, facilitating the growth of the steel industry elsewhere in Luxembourg, Lasauvage remained isolated and lost its competitiveness. Without viable logistics solutions, operations became increasingly unprofitable, leading to the permanent closure of the blast furnaces in 1877.

The Saintignon era and the revival of Lasauvage

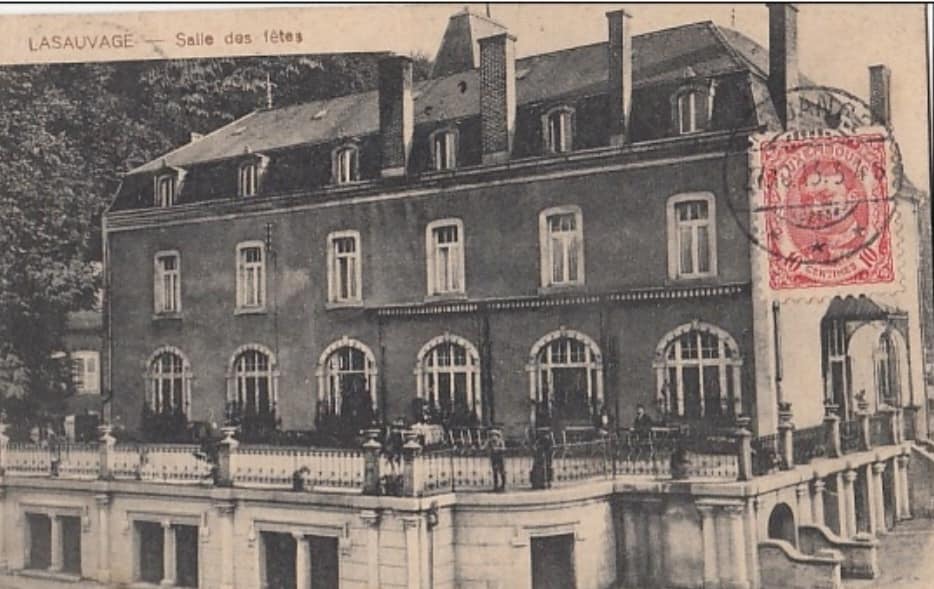

In the 1880s, Count Fernand of Saintignon gave the village a new lease of life. An industrialist and ironmaster, he invested in mining and exported the ore to his factory in Longwy for processing. To support this expansion, he provided the village with essential infrastructure: a church, a school, and a company store, increasing the population from ten to ninety-two families within a few years.

On the ruins of the old factory, he had a large building constructed that served various purposes throughout history, including a company store, an event hall, and a school. Today, this building houses preschool and elementary classes, the École-Nature, the Poppespennchen puppet theater and accommodation facilities.

This period marked the end of the iron and steel industry and the dawn of the mining era in Lasauvage, an activity that would endure for about a century.

A living heritage

Once a steelmaking center, Lasauvage preserved and celebrated its heritage. Nestled in a unique natural setting, the village blends history, culture, and education, offering visitors a glimpse into its industrial past.

Learn more / non-exhaustive bibliography:

- Rob Fleischhauer, „Lasauvage, le fer des nobles“, Korspronk N°26/2013

- Jacques Dollar, „Historique de l‘ancienne forge de La Sauvage »

- Armand Logelin-Simon, Lasauvage au temps de Fernand comte de Saintignon